More than 1,100 tern chicks have fledged from the artificial coastal bay island

A royal tern adult and chick on Maryland’s tern raft. Photo by Kim Abplanalp/Maryland Coastal Bays Program

Maryland’s tern raft hosted hundreds of terns again this year—including nesting pairs of two different state-listed-endangered species—and saw more than 350 tern chicks fledge during the island habitat’s fifth year in operation.

The wooden-framed artificial island has floated in Chincoteague Bay in Worcester County since 2021 and serves as a breeding habitat for colonial nesting waterbirds that are listed as endangered in Maryland. The populations of these waterbirds in the state drastically declined by as much as 95% since the 1980s due to habitat loss caused by sea level rise.

Through five seasons, the breeding platform has provided safe habitat for more than 1,100 common tern nests, with more than 1,100 tern chicks fledging from the site, making it the most productive breeding site for terns in the state.

In 2025, for the first time, royal terns also nested on the tern raft. From 29 nests, eight royal tern chicks fledged.

“Over five years this has become a big success—it’s producing equal to and in many cases higher than natural colonies,” Dave Brinker, a DNR Wildlife and Heritage Service avian conservation ecologist who helps to lead the tern raft project. “There’s more work to do, but in Worcester County, we’ve turned around a massive decline.”

The tern raft has seen hundreds of nesting pairs, resulting in more than 1,100 chicks fledged for state-listed-endangered birds.

The tern raft was built by the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, the Maryland Coastal Bays Program, and Audubon Mid-Atlantic to replicate nesting habitat that had declined in the area. In Maryland’s coastal bays, many small islands that had previously hosted nesting waterbirds have washed away. When the nesting platform was constructed in 2021, there were nearly zero nesting terns left in the coastal bays.

That year, crews bolted together eight platforms into a 32-foot-by-32-foot artificial island and covered the surface with crushed surf clam shells to mimic the sandy beaches where terns like to nest. They also added artificial grasses and chick houses for shelter.

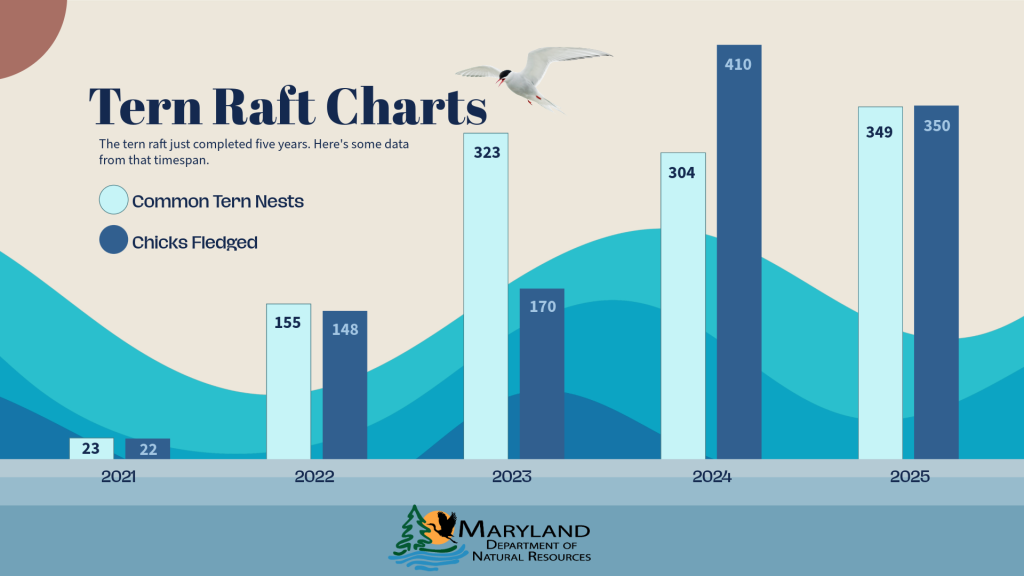

Before long, common terns arrived at the raft—attracted by decoy terns and speakers playing tern calls on the artificial island. The common terns built 23 nests that year, and 22 chicks fledged to maturity.

Since then, common terns have kept coming, and in steadily increasing numbers. In 2022, after staff expanded the raft to 48 feet by 48 feet, the platform hosted 155 nests, followed by 323 nests in 2023. And many of the same terns were nesting again on the artificial island, with often a close to 80% return rate, indicating that these birds had become strongly attached to the new breeding site.

“The work required to install, deploy, maintain and monitor the artificial breeding raft is significant, but to have this kind of success over the years makes it a very worthwhile endeavor,” Maryland Coastal Bays Program Executive Director Kevin Smith said. “I credit the success to the incredible partnership with our DNR colleagues and the loyal volunteers who come out year after year to help with this project.”

The tern raft floats in Chincoteague Bay, with a walkway to allow fledgling birds to climb back onto the raft from the water. Photo by Sarah Witcher/DNR

Terns migrate vast distances every year, breeding in the summer in the Caribbean, the United States, and Canada before wintering in Central and South America. Individual birds at Maryland’s tern raft have traveled from as far as Punta Rasa, Argentina, south of Buenos Aires.

Biologists with DNR and the Coastal Bays Program monitor the terns by banding juveniles and adults, in addition to counting nests and following the number of chicks that fledge. This year, DNR and Coastal Bays Program staff cordoned off a separate section of the raft for the royal terns so they wouldn’t crowd out the smaller common terns.

Every fall, staff and volunteers with the help of the Maryland Forest Service dismantle the raft segments and take them out of the water for the winter. In the spring they reverse the process, launching it into the coastal bays and reassembling the 18 segments into the floating island.

With the success of the tern raft, biologists are now looking to the next steps of establishing nesting colonies on islands and beaches in Maryland. Since nesting colonies establish every year at the raft, terns know to come to the area and can more easily move on to other nearby sites, Brinker said.

In 2024, DNR and the Coastal Bays Program restored 100 feet of beach as a nesting habitat on Reedy Island in Ocean City. This year, 39 breeding pairs of common terns successfully nested there, which Brinker said was only possible because of the nearby raft.

“An important part of the raft is maintaining a breeding population in Maryland so when we can take these next steps and improve habitat, the birds are local and they can just move next door,” he said. “If we hadn’t put the raft in, I think it would be a much bigger struggle to get founding birds to occupy this newly restored habitat.”

In the fall, the birds from the tern raft are well on their way to their next destinations. While many have already headed south, some chicks tend to explore far and wide in their first year of flying—and one fledgling from Maryland’s tern raft was recently spotted in Cape Cod, said Kim Abplanalp, the bird habitat coordinator with Maryland Coastal Bays Program.

But by next spring, many of these terns will likely be back in Maryland, and back in the bustling colony on the tern raft.

A common tern with its one-day-old chick next to a painted chick shelter on the tern raft this summer. Photo by Kim Abplanalp/Maryland Coastal Bays Program

By Joe Zimmermann, science writer with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources